Have you ever found yourself in the middle of a complex challenge, swimming in data or research, and you’re just not sure what to make of it? Conducting all of the research in the world is only as useful as our ability to make sense of it. With an emphasis on sense-making, the design thinking process includes an intentional approach on framing research and defining a path forward. In some ways, you can think of it like a string of lights…

Part I: The Scenario

It’s the first day of December. You and your family just got back from the tree farm where you spent hours dissecting every tree from every angle to find the perfect one for the living room. You just finished tightening the screws in the tree stand while your loved ones guided you with “Left! A little to the right! Perfect!” Music is playing, the family is laughing—everything is going smoothly, until…

It’s time for those damn Christmas tree lights.

You know what I’m talking about, right? Every year and without fail, holiday lights wind up in a tangled, disheveled mess. Untangling them has become an even bigger tradition than hanging up the mistletoe—kiss your blood pressure goodbye as you attempt to make sense of the shambled strands!

Even though we all know we’re going to go through the hassle of sorting the lights every winter, it’s still a daunting task. Everyone has that one box of lights stored in the attic filled with every kind of string imaginable: multicolor bulbs and classic white, indoor and outdoor, twinkling and continuous, working and not working (because of course you intend to find and replace that one bulb that burnt out three years ago). Without fail, the lights end up in a tangled mess. With so many bulbs at your disposal, where do you begin? It can be a real holiday headache.

Part II: The Metaphor

Believe it or not, a string of lights and design research have a lot in common.

When it comes to lights, everyone takes a different approach. Some of you may go straight for the ends while others begin sifting from the middle of the cluster. Some may plug the lights in to help guide them while others prefer to keep them off. Some of you may even throw the lights out and opt to get a new, nicely packaged set at the store.

Similarly, when it comes to data, there are many approaches on how to make sense of it. Some data may be sorted mathematically while other data makes more sense to sort artistically. Some data may be organized into a timeline while other data on a matrix. Regardless of the approach, the ultimate goal is to untangle the research data in a way that uncovers the brightest opportunities.

Part III: The Stuff that Matters

Let’s take a step back for a minute. You’ve done your research—conducted interviews, observed your audience interacting with your product, and looked at similar models for inspiration. All the while, you’ve been recording notes, drawings, photos, and transcripts. The vast amount of empathic data is intimidating, but it’s a good problem to have. You say to yourself, “This stuff is awesome. But what do I do now?”

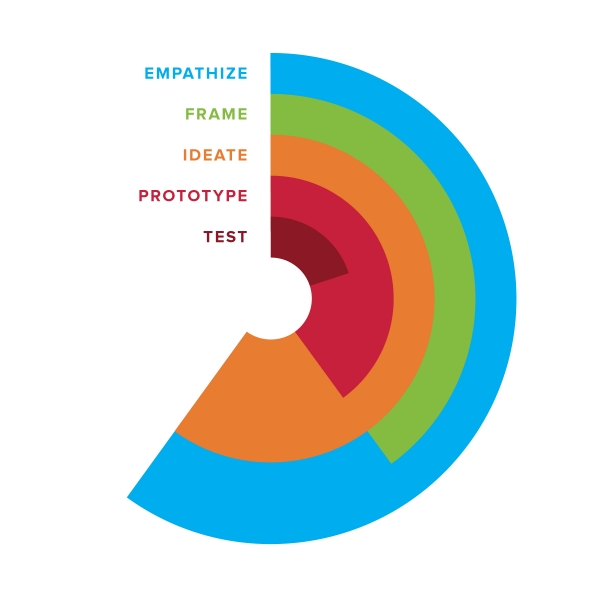

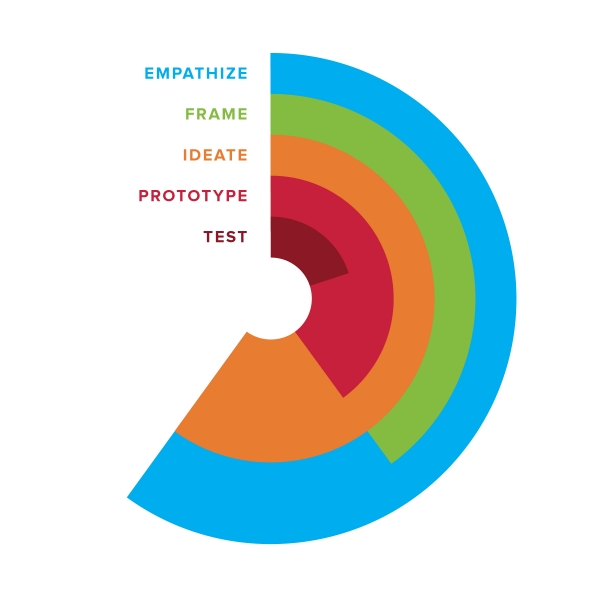

The next step in the design thinking process is to make sense of the data and uncover new opportunities. We call this phase the Frame Phase.

While it’s tempting to begin solving immediately after conducting research, synthesizing research data during the Frame Phase will uncover richer, more meaningful opportunities while also creating shared understanding on the opportunity-at-hand. It may feel impossible, sticky, or daunting at times, but don’t give up! Here are a few tips to get you started:

Step One: Make your data physical.

The first step in the framing process to to externalize all of your data. Get your research in a physical space so you can mold it, play with it, and organize it quickly. This could be on sticky notes, index cards, whiteboards or giant butcher paper. Getting data onto the wall also allows for collaborative sense-making to take place.

Step Two: Sort your data until it makes the most sense.

Data lends itself to different methods of sorting, and we all may sort the same data in a different way. The challenging part about the Frame Phase is that there are no right or wrong answers.

Time-based data lends itself toward journey mapping—charting audience’s activities across the course of an hour, day, or year. Journey maps can include not only the audience’s actions, but also their feelings, thoughts, and pain points. This type of sense-making puts your audience at the center of the story, allowing the team to solve for his or her most important needs.

Relational data lends itself toward affinity and/or venn diagramming—grouping data points as they relate to each other. Similar data points may be grouped together while contrasting ones be separated. This type of sense-making helps explain connections between your research.

Through sense-making, you’re looking to identify trends in your research and come up with insights.

Step Three: Record opportunities that you’ve found.

The last step in the Frame Phase is to make your insights actionable. We’ve found that turning insights (or problem areas) into questions allows us to connect our research to our ideas. “How might we…” statements serve as a launchpad for our ideas. For example, “How might we increase collaboration in our organization during the holiday season?” frames the problem (lack of collaboration) as an opportunity. These “How might we…” statements serve as generative questions for a team to brainstorm solutions, as well as test their solutions against.

Part IV: Tying It All Together

The Frame Phase has often been called the most challenging part of the design thinking process—and for good reason. Data gets messy, tangled, and confusing. However, when we embrace this feeling of overwhelm and prepare for it, we’re able to take the information in our hands and untangle it one strand at a time. It may take patience, a lot of practice, and an entire team, but at the end we find ourselves in the midst of glowing opportunities we can take into the next phases: ideation, prototyping, and testing

What will you find when you untangle the lights?