Over the past year, we have hosted several workshops for businesses and organizations throughout the Midwest who see the potential in implementing a human-centered design approach into their work and culture. People often appreciate the process, but have a hard time understanding how to incorporate it into their daily tasks once they leave. Participants often ask, “Is there a guide that will tell me when to use each of the methods?”

The answer is, not really.

The good news? There are many research options to get started and working examples of how different methods have yielded data towards solving specific problem spaces, but ultimately, there’s no prescriptive guide for when to use methods. This might sound like a cop-out but the reasoning lies at the core of human-centered design––it all comes back to your unique audience needs.

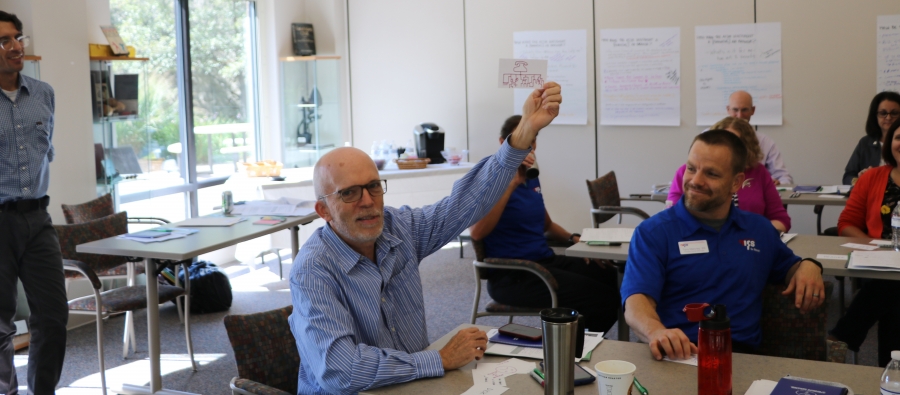

There are standard methods to choose from like interviews, surveys, mapping, observations and card sorting, but we encourage people to embrace the methodology. Don’t feel constrained by the methods you know––iterate, customize, gamify––whatever you need to do to relate to your audience and give and receive valuable input. Know that you may need to adjust and adapt on the fly, that’s okay! That’s part of the process. Try not to get caught up in forcing a method if it is not working. If interviews or surveys are not producing the data you need, reassess. Find out what’s missing and what you need to move forward. You may include analogous observations or immersing yourself in a particular environment to get more helpful information.

Don’t feel constrained by the methods you know––iterate, customize, gamify.

Part of the design process is coming up with a method that will best relate to your audience in a way that will get you the information you need. For example, if you need to customize messages to specific audiences, you may want to interview folks and build out personas. While this means methods are customized for every problem space, there are some common things to think about:

- What is it that you want to learn?

- How many different audience types will you need to interact with?

- How does your audience best communicate?

- Are you able to have direct communication with them or do you need to explore appropriate indirect methods?

- How can you relate the experience to something familiar and comfortable for them?

- What are the limitations of the intended method?

- How much time or budget is available?

The most important thing to remember is to empathize with the people whose problem you’re striving to solve. Explore different methods, practice them with friends or co-workers to build out techniques and applications, and adapt them to work for you.