The reality of modern business is one of ever-accelerating evolution and change.

New technologies can uproot and transform entire industries, from new service models to new devices to new ways of working. These realities put tremendous pressure on organizations to adapt quickly.

But evolving just to keep up can be messy and aimless. Rethinking your business, however, should be intentional — and that’s why we at SmallBox use the design thinking process.

Design thinking is a problem-solving methodology that puts people — specifically, your audiences — first. One of the benefits of this human-centered approach is that it’s empathy-heavy on the front end.

Design thinking prioritizes understanding audiences before jumping to solutions.

Design thinking prioritizes understanding audiences before jumping to solutions. For example, an association wouldn’t want to design a service or program without first understanding its members’ challenges, needs and goals.

In the same vein, evolving your business should not be tackled without first taking a look at the holistic experience — the experiences of your employees, your clients, your partners and your constituents. Each audience’s experiences and expectations are different: How do you even begin to tackle all of them?

Building transformational experiences

One of the first and hardest steps for businesses is to let go of control, to not jump in and start solving or building based on assumptions. Again, before an organization can meaningfully evolve, it must first seek to understand all of its audiences and their experiences.

That’s just part of why SmallBox deploys the design thinking process when working through these challenges with our clients. Design thinking begins with empathy — listening and learning from the people we are designing for.

A few things you’ll need to begin building transformational experiences: a toolkit of creative exercises, a methodology focused on human-centeredness (design thinking), a mindset tuned to embrace collaboration and sometimes fuzzy spaces, and an encouraging partner to guide and see you through.

SmallBox sees all projects with our partners as opportunities for learning and evolution — it’s a concept we call transformational learning experiences.

SmallBox uses these opportunities to help partners not only identify and solve complex challenges (which more often than not relate to member or constituent experience), but to also bolster the team’s internal processes and way of working (employee experience).

For example, while working with a university’s alumni association to improve its members’ experience, we facilitated a number of sessions with the team following the design thinking framework. Along the way, that team has learned how this methodology can be applied to their day-to-day work, helping to broaden their thinking and deepen their collaboration skills internally.

In this way, we strongly believe in teaching the way we do (one of our internal team mantras is “teach as we do”). This means we:

- Help you find and seize opportunities to innovate your services, offerings and processes,

- Work with you to build and sustain an environment where collaboration and creativity thrive,

- Teach you human-centered methodologies, and

- Provide you with tools to solve such challenges on your own

Sure, our projects often do result in a refreshed brand or a new website — but how we get there is just as important as these outputs. Our goal is to empower our partners to eventually solve these fuzzy challenges on their own.

Our goal is to empower our partners to eventually solve challenges on their own.

What it looks like in action

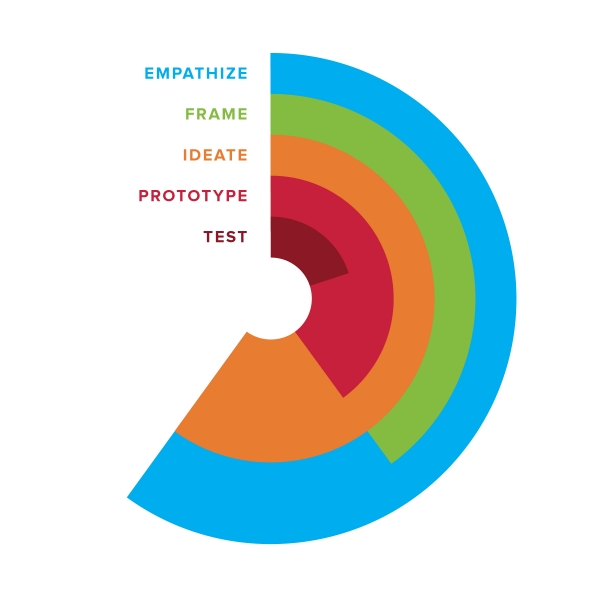

Our process often begins with a workshop or Factory Day focused on introducing your team to the design- thinking methodology through the lens of a general challenge or one specific to your organization. Then, following the design thinking process, we’ll work through a series of sprints and collaborative sessions focused on empathy, framing, ideation, prototyping, and testing to solve the challenge.

Worth noting is that these steps don’t always occur linearly. Sometimes it’s necessary to go back a step, or to work on two concurrently. One thing that doesn’t change: we always start with empathy, learning as much as we can about audiences before jumping to solutions.

Here are some examples of recent SmallBox projects:

- Membership experience design with American College of Sports Medicine

- Rebrand with Regenstrief Institute

- Course design with Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis

Want to learn more about design thinking? Join us for our next public workshop, A human-centered approach to problem solving, on Dec. 9. To register, visit our landing page.