For many years, SmallBox has started our major projects with what we’ve called a “Discovery” phase. This is an essential first step because we’ve learned from experience that our ideas, designs, and project outcomes are all stronger when we go through an intentional research process. To do our best work, we need to empathize before solving.

What is Empathy?

em·pa·thy

Noun

the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.

Sometimes called design research, or an empathy phase in a human-centered design process, this focus is all about understanding the experience, perspective and emotions of your audiences, then applying what you’ve learned to your services or products.

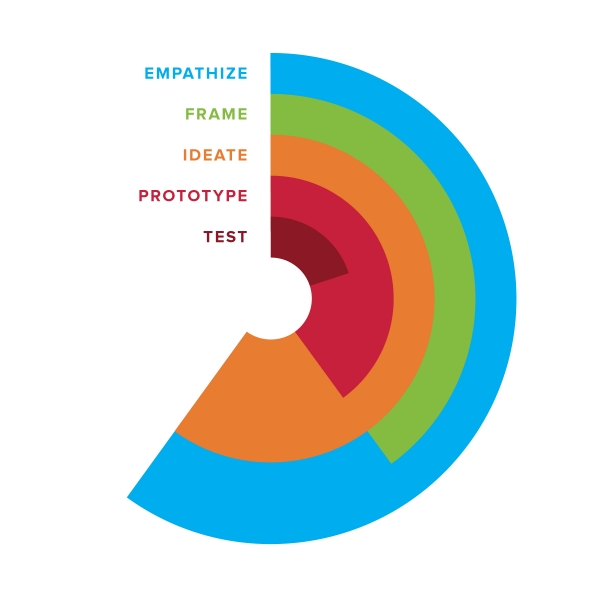

Here’s the design thinking process we use at SmallBox:

But in reality it looks more like this:

While the process is non-linear and can move back and forth from one phase to another, it always starts with empathy. And for good reason.

Why is empathy important?

Empathy leads to…

- Greater understanding of the people you serve.

- Dispelled assumptions and biases about how and why people interact with your service or product.

- Creating more meaningful solutions that are more readily adopted.

- Becoming more responsive to audience needs.

- Operating your business in a human way.

Conducting design research to truly empathize with people may seem like it takes a lot of time, or slows down your process. It’s seductive to just jump in and start solving right away. However, the time spent up front can save a lot of time later. Without really understanding your audience needs, you could waste resources creating a new offering that doesn’t resonate or actually meet those needs.

Having your audiences take part in the process from start to finish fosters buy-in for both the cause and the solution. It allows for transparency that ultimately creates shared understanding and a wider variety of potential solutions.

Listening and observing can help you discover unmet needs and possibilities you never knew existed. You might miss a huge opportunity that someone else eventually spots and acts on.

How to get started

Here are some basic first steps to incorporating empathy into your work:

- Identify groups of people who are critical to your success. This might be your team, your customers, or key partners. You may already have strong awareness of who your audiences are and know how to reach them – if so, you’ve got a head start!

- Ask yourself what you don’t know know about the people you care about. Are you basing everything you know off of one thing one person said five years ago? Sometimes it is hard to be honest with ourselves. We have cognitive biases that help us confirm long held opinions. Step back, take a critical look at what you think you know about your audiences, and make note of any assumptions you are making.

- You can start simply with listening. Interviewing is a foundational skill for empathy research. Use your assumptions list to create a bank of questions to prepare for interviewing your audiences. Make sure to approach these conversations with curiosity and a commitment to staying neutral (remember those cognitive biases we mentioned earlier?). What you can learn through a series of thoughtful, objective interviews can be eye opening.

- Tap into the power of observation. If you have never watched people interact with your product or service, make a point to do so. Observation can paint a whole new picture – sometimes showing things we might never know to ask, or a person might not think to bring up in an interview.

While there are many advanced and creative empathy research methods – everything from contextual inquiry to diary studies – it’s okay to start with basics.

What does it look like?

In the book Creative Confidence, co-authors Tom and David Kelley mention a scenario of researching how to improve the ice cream scoop. Most people, when asked to talk through their process, shared the basics of how they used the scoop to get ice cream – get the scoop out of a drawer, warm it with water, start on one far side of the container and scoop toward the other, etc. But most people failed to mention that they licked the scoop before tossing it into the sink. It was either an unconscious thing, or they didn’t feel it was important enough to mention. By engaging in empathy research and observing people in action as they scooped ice cream, this detail emerged.

Knowing people will lick the scoop changes everything.

Having moving parts (as some scoops do) becomes a lot less desirable. Without empathy, they would have missed this detail all together, and maybe built the wrong kind of scoop. Getting to these details, as mentioned earlier, is why empathy is so important and useful.

The more I practice empathy research, the more I see it as a gift that keeps on giving. More depth in understanding about your audiences. Greater insights in how to serve them. A more informed, human-driven experience or product designed to elicit a positive response from the people who matter the most – your audiences, customers and employees!